What is it about the sea that beckons us to retreat, to seek solace in its vast, indifferent expanse? In The Sea, The Sea, a novel by Iris Murdoch, the ocean is a mirror to the internal landscape of the human psyche — endless, chaotic and sometimes unsettling. Blending psychological depth with metaphysical inquiry, Murdoch crafts a story that is as much about the mysteries of the mind as it is about the sea that frames it.

Charles Arrowby, a retired theatre director who has spent his life orchestrating illusions for the stage, retreats to a house by the sea, hoping to escape the very forces that shaped his identity. But like the tides that shape the shoreline, his attempt to flee from himself only draws him deeper into the swirling currents of obsession, memory and self-deception.

The Sea and the Self

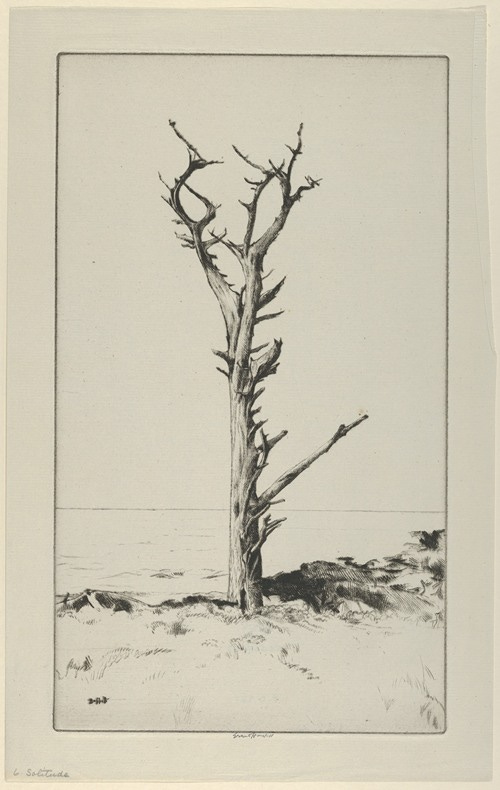

There’s an odd, elusive comfort in solitude that Arrowby seeks — a belief that by removing himself from the world, he can finally hear his own voice. By distancing himself from others, he believes he can access the “real” self beneath the masks. But when the distractions fade, what he encounters is not clarity but distortion: the echo chamber of his own mind, louder than any external clamor.

“We have the ‘heartlessness’ of monks; and in this respect we suffer the changes characteristic of ordinary life with a difference, in a sublimated symbolic way.”

Arrowby’s attempt to transcend the ordinary becomes a battle with himself. The sea, in its endless rhythm, mocks his desire. It is not a place where answers are found, but where one must confront their own shifting shadows. His belief that he can control the environment and therefore the self, is undone by the unpredictability of both the natural world and his own mind.

What he imagines as a spiritual cleansing becomes instead a site of confrontation. The sea reflects. And what it reflects is deeply uncomfortable.

The Mirage of Control

In the stillness of his coastal retreat, Arrowby begins a slow unraveling. With no audience and no performance to give, he turns inward and begins editing his own story. Memory becomes malleable. He revisits old relationships, especially with Hartley, the woman he once loved, reconstructing their meaning with the precision of a stage director rearranging a scene.

“I can tell you, reader, about my past life and about my ‘world-view’ also, as I ramble along. Why not? It can all come out naturally as I reflect.”

There is a confession of helplessness, but also an evasion of responsibility. Arrowby resents the idea that life has happened to him. Rather than acknowledging the ways in which he has shaped or distorted it. Instantly, the retreat becomes a space for elaborate self-deception. He wants to believe he’s orchestrating a final act of insight. What he’s really doing is clinging to an old script.

The sea, with its relentless motion, reminds him that control is always provisional. His desire to fix things in place especially the past collides with the fundamental nature of both memory and the ocean: they shift, they erode, they refuse to be held still.

The Undercurrent of Obsession

Obsession is the undercurrent of Arrowby’s withdrawal. It builds slowly, then begins to saturate everything. His thoughts circle Hartley, his first love, with increasing intensity. He imagines her as a lost ideal, someone who could restore a sense of purity to his fragmented self.

“I left in store with that first love so much of my innocence and gentleness which I later destroyed and denied, and which is yet now perhaps at last available again.”

But this is not a love story. Arrowby does not love Hartley as she is now — older, changed, autonomous. He loves the image of her that he has preserved, untouched by time or complexity. His obsession isn’t about her, it’s about himself. Arrowby wants her to confirm his story, to validate his sense of who he was and who he still might be.

“I was sane enough to know that I was in a state of total obsession and that I could only think, over and over again, certain agonizing thoughts, could only run continually along the same ratpaths of fantasy and intent.”

This is what Murdoch captures so precisely — the way obsession disfigures our perception of others. We begin to see not the person, but the projection. Arrowby’s tragedy is that he cannot separate memory from reality. And in the absence of clarity, he becomes increasingly dangerous…not only to himself, but to those he claims to love.

The Illusion of Solitude

Arrowby believes that solitude will offer him truth. But instead, it brings a kind of madness. Without the checks and balances of other minds, his thoughts grow increasingly erratic. His journal, which begins as a reflection on peace, spirals into confession, justification, delusion.

“I was never alone. This is the first house which I have owned and the first genuine solitude which I have inhabited. Is this not what I wanted?”

Murdoch challenges the romantic idea that solitude leads to enlightenment. In her view, it can just as easily lead to narcissism. Arrowby’s isolation does not purify his soul, it amplifies his flaws. Without others to see, confront or care for, he collapses into himself.

For Murdoch, ethical growth depends on the friction of relationship. On truly seeing others as they are, rather than as extensions of ourselves. Arrowby’s failure is not his retreat, but what he refuses to confront within it.

The Sea as Mirror and Force

Critics often see the sea as a symbol of the unconscious. But in Murdoch’s hands, it becomes something less abstract, more elemental. The sea does not respond to human desire. It is not a stage or a metaphor. It simply is.

“The sea is golden, speckled with white points of light, lapping with a sort of mechanical self-satisfaction under a pale green sky. How huge it is, how empty, this great space for which I have been longing all my life.”

The sea in this novel is terrifying precisely because it refuses to cooperate. It absorbs human emotion without reflection. Its power is in its presence, its ability to dwarf the human scale, to endure without meaning. For Arrowby, the sea becomes a kind of judge — not because it offers punishment or absolution, but because it offers nothing at all.

The sea becomes a companion to the unconscious. It too is deep, unknowable and dangerous when misunderstood. It reflects what we cannot avoid.

The Tides of Understanding

By the novel’s end, Arrowby is no wiser, only more exhausted. His retreat has not led to epiphany, but to exposure. He is no longer performing, but neither is he free. He has come face-to-face with the limitations of self-knowledge, and with the fact that solitude cannot strip us of our illusions unless we are willing to surrender them.

“Now, I realized, it was done; and my desire was like a river which has forced its channel to the sea.”

But in the looking, in the willingness to face our own turbulence, there is something like grace.

You might like this…

Until next time!❤️

Fascinating. As someone who has lived off grid in a cabin in the woods for the last 7 years I find much to resonate with here.

I have not read Murdoch's book but perhaps it might be worth a look.

That said, the forest is a different animal to the sea. Thanks for the sub. I will happily reciprocate after reading this piece. Fine writing.

Loved this. Iris Murdoch is one of my favourites.