The story of the Pied Piper is one of those narratives that feels wrong from the first time you hear it. On the surface, it’s simple. But the more you examine it, the more unsettling it becomes not just in its cruelty, but in its ambiguity.

The Historical Roots of the Pied Piper of Hamelin

So, the most common version of the tale goes like this:

Set in the town of Hamelin, Germany in 1284, the story recounts the arrival of a mysterious figure, typically clad in vibrant, multicolored attire, who was enlisted by the desperate townspeople to eradicate a severe infestation of rats.

Through the enchanting melody of his pipe, the piper successfully lured the vermin out of Hamelin and into the nearby Weser River, where they met their watery demise. However, the narrative takes a dark turn when the citizens of Hamelin, overcome by greed, allegedly refused to compensate the piper for his invaluable service.

Enraged by this betrayal, the piper returned to Hamelin on the feast day of Saint John and Paul, June 26th, and played his pipe once more. This time, the captivating music lured away a significant number of the town's children – accounts vary, but the figure of 130 is frequently cited – who were never seen again.

Interestingly, the element of the rat infestation wasn’t always part of the tale - it only appeared around the 16th century. Earlier versions focused solely on the mysterious disappearance of the children. This shift suggests the story evolved over time, shaped by historical fears like plagues.

While the Black Death came later, its devastation left a mark on Europe’s imagination, likely fueling the connection between rats and disaster. It’s a great example of how folktales adapt, absorbing the worries and realities of each generation that retells them.

The Oldest Accounts of the Pied Piper in History

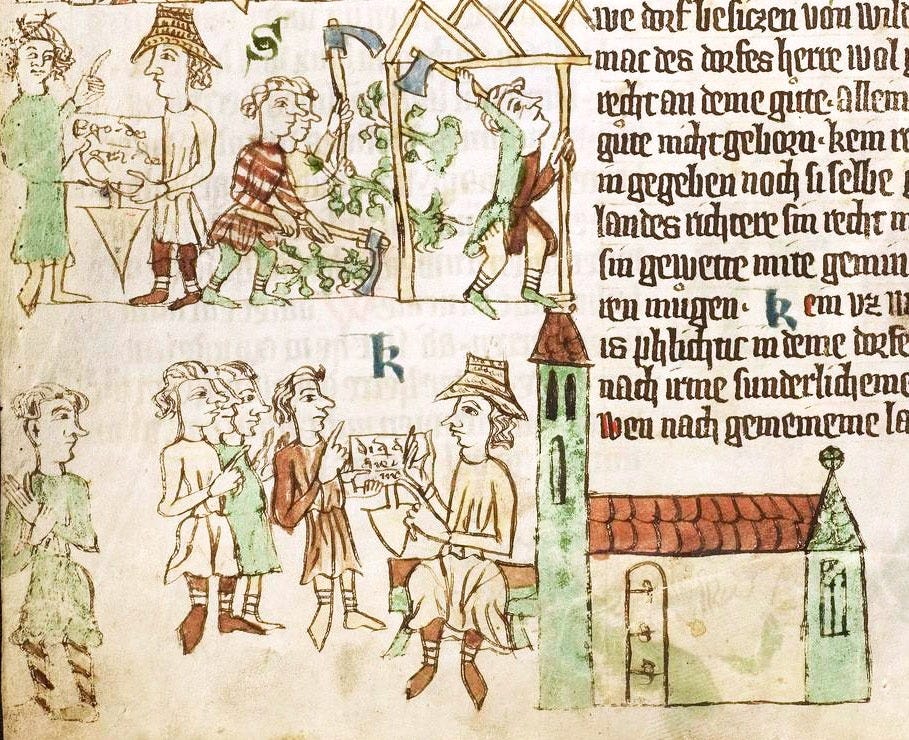

The earliest known reference to the Pied Piper story is widely believed to be a stained-glass window that was installed in the Church of Hamelin around the year 1300. Although this significant piece of historical evidence was unfortunately destroyed in 1660, detailed descriptions of it from the 14th to the 17th centuries have survived, allowing for a modern reconstruction by historian Hans Dobbertin.

The depiction on the window featured the distinct figure of the Pied Piper dressed in colorful clothing and several children attired in white.

This near-contemporary memorial, created within a century of the supposed event, is generally regarded by historians as a commemoration of a tragic historical event that befell the town. The prominent placement of such a memorial within a church, a central institution in medieval society, strongly suggests that a significant and memorable incident involving the loss of children occurred in Hamelin around 1284.

Churches in the Middle Ages often served as vital repositories of communal memory, and significant losses or events were frequently memorialized through artistic representations like stained-glass windows. The depiction of the children in white on the stained-glass window may carry symbolic weight, potentially representing their innocence, purity, or even serving as a visual metaphor for death in medieval iconography. While white often symbolized purity and was associated with religious figures, it could also, in certain contexts, represent mourning or the afterlife.

The earliest written record of the Pied Piper story is found in the town chronicles of Hamelin, with an entry dating back to 1384. This entry reportedly states, "It is 100 years since our children left".

This statement, made a century after the supposed events of 1284, indicates that the disappearance of a significant number of children was a deeply ingrained memory within the community. Further evidence of the legend's historical resonance can be found on the stone facade of a private residence in Hamelin known as the Pied Piper house, which dates back to 1602.

An inscription on this house's window provides more specific details, stating: “A.D. 1284 – on the 26th of June – the day of St John and St Paul – 130 children – born in Hamelin – were led out of the town by a piper wearing multicoloured clothes. After passing the Calvary near the Koppenberg they disappeared forever”.

A similar inscription was also reportedly located on the town hall. Additionally, a street in Hamelin, known as "Bungelosenstrasse," which translates to "street without drums," is traditionally believed to be the last place where the children were seen. Legend has it that music and dancing are forbidden on this street in remembrance of the lost children.

The consistent mention of June 26, 1284, and 130 children across historical records suggests a strong oral tradition preserving the memory of a significant loss in Hamelin. The existence of "Bungelosenstrasse" and its tradition of silence further reflects lasting communal trauma and a desire to commemorate or appease the vanished children.

Hamelin in the 13th Century

Hamelin's history traces back to a monastery founded as early as 851 AD, with the surrounding village evolving into a town by the 12th century. During the 13th century, the period in which the events of the Pied Piper story are typically placed, Hamelin underwent a notable transformation.

Initially a market center dependent on the Abbey of Fulda, a relationship that lasted until 1259, Hamelin was granted a charter around the year 1200. This chartering marked a significant step in its development as an independent urban entity.

By the latter part of the 13th century, specifically in 1284, the year associated with the Pied Piper incident, Hamelin had become part of the territory controlled by the dukes of Brunswick and also joined the influential Hanseatic League. Membership in the Hanseatic League indicates the town's growing importance as a commercial center within the region, highlighting its increasing economic connections and influence.

Hamelin's shift from a primarily religious settlement to a more commercially oriented town during the 13th century may have brought about social and economic changes that could have indirectly contributed to the circumstances surrounding the legend. Periods of significant societal transition can often generate anxieties and tensions that find expression in folklore, reflecting the community's attempts to understand or cope with new realities.

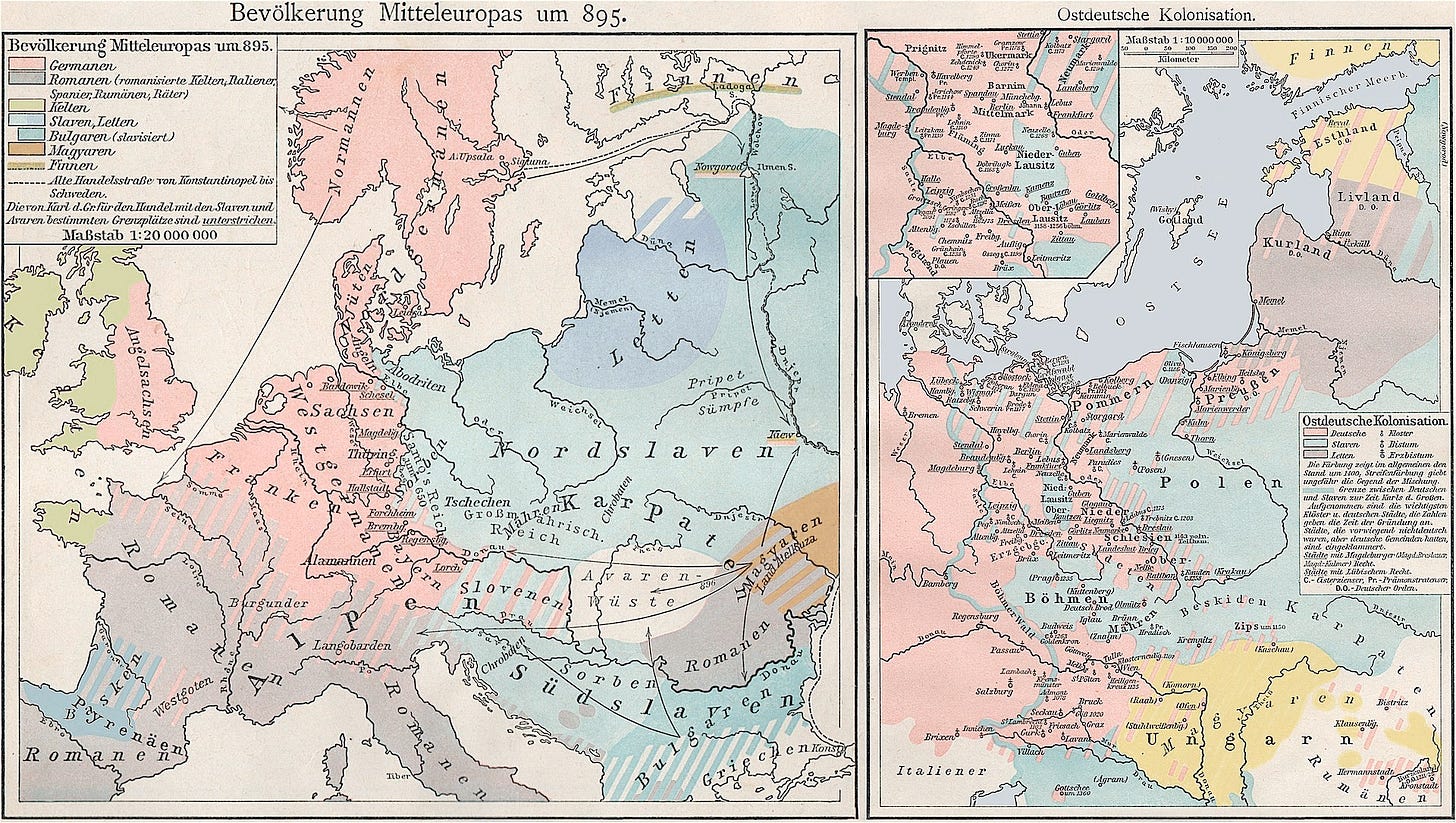

The 13th century in Germany was also marked by a significant historical phenomenon known as the Ostsiedlung, or eastward expansion. This was a period of large-scale migration of Germanic populations from the more densely populated regions of the Holy Roman Empire to settle in the less inhabited lands to the east, particularly in areas that now constitute parts of Poland and Brandenburg, including the region around Berlin. This eastward movement gained momentum after the Danish defeat at the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227, which opened up territories south of the Baltic Sea for German colonization.

Theories of Disappearance

The Children of Hamelin Seeking New Lands?

Among the various interpretations attempting to explain the historical basis of the Pied Piper legend, the migration theory, deeply rooted in the context of the medieval German eastward expansion (Ostsiedlung), stands as one of the most widely accepted among historians.

This theory posits that the "children" mentioned in the tale may not have been solely young children but rather a broader group of young adults or unmarried individuals seeking new opportunities in the less populated eastern territories.

Research conducted by linguist Jürgen Udolph has found connections between surnames prevalent in Hamelin during that period and families in regions north of Berlin, including Prignitz and Uckermark, suggesting a possible migration towards the Brandenburg and Berlin areas.

In this interpretation, the Pied Piper figure is not viewed as a vengeful sorcerer but rather as a "locator," a recruiter hired by noble landowners to attract settlers to these eastern regions. Economic and social pressures within Hamelin itself, such as overpopulation or limited opportunities for younger generations (as suggested by the majorat system where the eldest son inherited land), could have further motivated such an emigration.

The potential destinations for these migrants could have included various regions involved in the Ostsiedlung, such as Brandenburg, the Berlin area, Pomerania, East Prussia, and even Transylvania, as mentioned in some versions of the tale.

The migration theory effectively addresses the specific date and the reported number of missing individuals by placing them within the historical context of a known period of significant population movement from Germany to Eastern Europe, a large-scale phenomenon during which the year 1284 falls.

Furthermore, the relative lack of detailed contemporary documentation regarding the departure of these "children" might be explained by the fact that migration was a common occurrence at the time, and the individuals involved may have been considered adults or young people making their own decisions, rather than children being forcibly abducted. Historical records often prioritized the documentation of unusual or extraordinary events.

Disease or Plague?

Another prominent set of theories centers around disease and epidemics. One interpretation suggests that the Pied Piper figure may represent a personification of Death during a plague. While the Black Death, a devastating plague often associated with rats, reached its peak in Europe after 1347, more than half a century after the events in Hamelin, the general association of rats with disease in medieval beliefs could have led to the later inclusion of the rat infestation in the Pied Piper narrative as a symbolic representation of an earlier epidemic.

Some scholars have even proposed a specific disease, such as murine typhus, as a potential cause of death for the children in Hamelin in 1284, citing the association with rats and the possibility that the Piper's "pied" (mottled) clothing could symbolize the skin lesions caused by such an illness.

The Piper's "pied" clothing might also be interpreted in this context, perhaps related to the visual manifestations of certain diseases, such as splotchy skin. While the Black Death occurred after 1284, the established connection between rats and disease in medieval folklore could explain the later addition of the rat element to the Pied Piper story, potentially symbolizing a different, earlier epidemic.

Mass Hysteria?

Additionally, the theory of the "dancing plague" (choreomania), a form of mass hysteria that caused uncontrollable dancing, has been proposed as an explanation for the children being led away in a trance-like state. Outbreaks of dancing mania are documented in medieval history, including one in Erfurt, Germany, in 1237, where a large group of children reportedly danced their way out of town, a scenario bearing some resemblance to the Pied Piper legend.

Furthermore, the dancing plague theory offers a compelling explanation for the seemingly irrational act of children following a piper out of town, suggesting a possible historical instance of mass psychogenic illness, as outbreaks of this phenomenon are recorded in medieval history and share similarities with the Pied Piper narrative.

Children's Crusade?

Other theories link the disappearance to historical events such as the Children's Crusade of 1212, comparing the Pied Piper to Nicholas of Cologne, who led thousands of children on an ill-fated journey. However, the timeline of the Children's Crusade precedes the 1284 date associated with the Pied Piper incident.

Another theory suggests that the story might have originated with young men from Hamelin who were killed at the Battle of Sedemunder in 1259. The specific date of June 26th has also led to speculation about a possible pagan midsummer celebration that may have gone tragically wrong.

The comparison to the Children's Crusade highlights the historical context of religious fervor and the potential for large-scale movements of young people during the Middle Ages, although the timing does not perfectly align with the Pied Piper narrative.

Murder, Cult, Rituals?

More ominously, some interpretations propose darker scenarios, with the Piper depicted as a pedophile or murderer who lured the children away for nefarious purposes. Another theory suggests that the children may have been enticed away by a heretic sect for ritualistic practices.

These darker interpretations likely reflect societal anxieties surrounding the vulnerability of children and the potential presence of malevolent individuals within communities, shaping the narrative over time as folklore can sometimes serve as an outlet for expressing and processing deep-seated fears.

Deeper Meanings in the Narrative (Symbolism & Folklore)

Rats

In medieval beliefs, rats were generally associated with negative connotations, representing disease, pestilence, and uncleanliness. They were often blamed for the spread of illnesses, most notably the bubonic plague. However, in some cultures, rats were occasionally viewed differently, sometimes revered as trickster deities or symbols of abundance.

The appearance of "rat kings," a phenomenon where multiple rats' tails become entangled, was often considered an omen of disaster or chaos. Given the predominantly negative symbolism of rats in medieval Europe, the later addition of the rat infestation to the Pied Piper story likely served to amplify the sense of Hamelin being afflicted by a serious problem, potentially linked to disease or even divine punishment. Symbolism in folklore is often deeply embedded in cultural beliefs and values, and the rat's image as a carrier of disease would have resonated strongly with medieval audiences.

The Pipe

The pipe, the instrument played by the central figure, was a common musical instrument during the Middle Ages, encompassing various types such as flutes, recorders, and bagpipes. The combination of pipe and tabor was frequently used to provide music for dancing, ceremonies, and folk customs. Bagpipes, another type of pipe, were associated with both folk and military music.

In later periods, clay pipes became associated with storytelling, wakes, and social gatherings. In the Pied Piper legend, the pipe possesses a seemingly magical quality, capable of influencing both animals and people. While appearing magical in the narrative, the pipe could also be interpreted symbolically as representing persuasion, leadership, or even a call to a different way of life, aligning with the migration theory where the piper acts as a recruiter.

Musical instruments have historically been associated with charismatic figures and the ability to sway emotions and actions. The ambiguity surrounding the specific type of pipe played by the Pied Piper (fife, recorder, bagpipes are mentioned in different contexts) likely reflects the general use of the term "pipe" to refer to various woodwind instruments during the medieval era.

Multicolored Clothing

The Piper's distinctive multicolored, or "pied," clothing is a recurring and significant detail in the legend. Color symbolism held considerable importance in the Middle Ages, with different colors often conveying specific meanings.

For instance, purple was associated with royalty, red with power and blood, blue with heaven, green with hope and danger, yellow with wealth and betrayal, black with mourning and authority, and white with purity. Bright colors could also indicate higher social standing or specific professions.

Significantly, locators during the Ostsiedlung were often described as wearing colorful attire to attract the attention of potential settlers. The term "pied" was also sometimes associated with jesters and, as mentioned earlier, potentially with the splotchy skin lesions of certain diseases.

The Piper's multicolored clothing most likely signifies his role as someone outside the conventional social structure of Hamelin, perhaps a traveling entertainer, a recruiter from elsewhere, or even a symbolic figure. The use of distinctive attire often denoted specific roles or social positions in medieval society, and the connection to the attire of locators further strengthens the migration theory.

The contrasting interpretations of multicolored clothing, ranging from representing wealth and status to trickery and disease, highlight the inherent ambiguity within folklore and the potential for different audiences to interpret symbols in various ways.

Evolution and Variations of the Pied Piper Story

An examination of the Pied Piper story across different historical periods and versions reveals several key differences and evolutions in the narrative. Early mentions of the tale, such as the stained-glass window (c. 1300) and the Hamelin town chronicle entry of 1384, primarily focus on the disappearance of the children and do not include any reference to a rat infestation.

Furthermore, the destination to which the children were led differs across various versions, ranging from a cave or mountain to the mythical land of Transylvania, a beautiful realm, or even being drowned in the Weser River, mirroring the fate of the rats.

The overarching moral of the story also seems to have evolved over time. While the earliest mentions appear to serve as a commemoration of a tragic loss, later versions often emphasize the cautionary aspect of the tale, highlighting the consequences of breaking promises and the dangers of greed.

The evolution of the story, particularly the addition of the rats, suggests a process of narrative accretion, where new elements were added over time, possibly to enhance the dramatic impact or to reflect shifting societal concerns. This is a common characteristic of oral traditions and folklore.

Despite these variations, the core elements of the narrative – the piper, the children, the specific date of June 26, 1284, and the number of 130 missing children and their unexplained disappearance – remain consistent, suggesting a potential historical event at the core of the legend.

Towards a Historical Understanding of the Pied Piper Legend

The most widely accepted theory links the event to the medieval German eastward migration (Ostsiedlung), suggesting the Pied Piper was a recruiter, or "locator," leading young people to new settlements. Economic pressures in 1284 support this idea. Other theories include disease outbreaks, possibly influencing the later association with rats, and mass psychogenic illness, like the dancing plague, as a potential cause for the children’s disappearance.

Hamelin's historical markers, such as inscriptions and the silent street "Bungelosenstrasse," reinforce the town’s long-standing connection to the legend. However, without definitive proof, the true fate of the lost children remains a mystery.

What do you think really happened to the children of Hamelin? Were they taken, lost or did something else occur?

Until next time!❤️

Goodness, this is a really thought provoking post. I firmly believe that mythology is code for history, we just have to uncover the key. You've given lots of potential keys here. Most significantly , the migration theory seems to hold water, especially with the "pied" or colourful clothing as you describe. However, one thing haunts me - the "memorable incident involving the loss of children occurred in Hamelin around 1284." As you've described, this was a "memorable incident". If it was simply migration, it would be tragic and concerning to the community, but the community apparently went to great lengths to commemorate this particular event when they "lost the children". This speaks to something more. Perhaps it was the dancing plague? Goodness, apart from the tarantella, I didn't know there was a word for this! But regardless, it seems to point to some particular traumatic event, maybe in the context of migration, when something else - something awful like perhaps drowning in the river, or worse, that happened to these children. Although it was centuries ago, I think it's still important to attempt to uncover what it was that made that community mourn those 130 children. Modern day slavery is a real thing, we can learn lessons from the past.

Gut geschrieben - well written! Thank you for the thorough analysis and presentation of the possible truths behind the myth, as well as the helpful commentary on the characteristics of fairy tales and their tendency to morph through time.