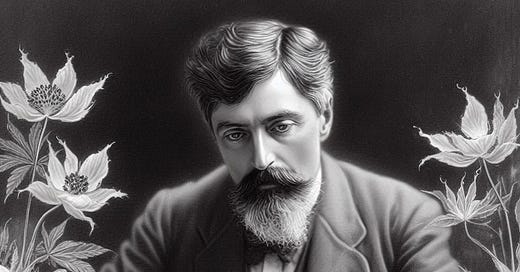

It’s difficult to read Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater without a sense of disorientation. Not because the language is dense, although it sometimes is…and not because the subject matter is difficult (though that, too, is undeniable). The disorientation comes from something deeper.

A structural ambiguity that resists the reader’s instinct to sort, to divide, to name. This is not a moral tract. It’s not a cautionary tale. It’s also not quite autobiography in any conventional sense. It is, at its core, a study in how a mind experiences itself when the borders of time, memory and identity begin to blur.

And De Quincey does not merely describe this blurring. He writes from inside it.

Opium Is Never Just Opium

From the beginning, opium appears in the text not as a straightforward agent of decay or delight but as something much stranger - a medium, almost, through which De Quincey apprehends new dimensions of perception. He doesn’t take the drug to escape reality in the cheap, dismissive sense. He takes it to magnify reality, to dilate consciousness, to enter a mode of attention that makes the everyday feel newly layered and alive in unsettling ways.

“Thou hast the keys of Paradise, oh just, subtle, and mighty opium!”

This invocation is often quoted, often isolated. But within the larger rhythm of the text, it doesn’t strike a celebratory tone. It reads more like an acknowledgment…perhaps even a surrender. Paradise, in De Quincey’s vision, is not some serene pleasure dome. It’s a threshold space, suspended between euphoria and disintegration. That opium holds the keys to this place doesn’t mean the door should be opened. It just means that it can be.

There is, throughout the Confessions, a reluctance to frame experiences of intensity: ecstasy, terror, insomnia, reverie as symptoms in need of correction. De Quincey is far more interested in what they reveal. And what they reveal is often uncomfortable. Dreams become so enormous they eclipse the waking world. History invades the psyche. Childhood returns not as nostalgia, but as a dislocated reality. The past doesn’t pass. It reanimates itself. Not symbolically, but viscerally.

The Logic of Opium Is Not Linear

The book is structured in a way that reflects the conditions it describes. It begins with autobiography: poverty, wandering, loneliness in London…but doesn’t stay there. As the opium use intensifies, so does the instability of the narrative. The prose swells, the paragraphs lengthen, the sense of chronology evaporates.

You can feel the shift in the pacing. The early pages offer fragments of Dickensian hardship: hunger, shabby clothes, casual cruelty. But these are not dramatized for sentimentality. If anything, De Quincey recounts his suffering with a sort of bemused detachment. It’s the inner world that really animates him. And once opium enters that world, everything else begins to recede.

What replaces it is not exactly dream, and not exactly thought. Something hybrid. Consider the scene in which De Quincey describes descending into endless chasms, where time, memory, and reality disintegrate. The detail is precise, but the logic is suspended. Time no longer moves forward…it loops and distends. The imagery doesn’t lead to meaning. It leads to more imagery.

“I seemed every night to descend, not metaphorically, but literally to descend, into chasms and sunless abysses, depths below depths, from which it seemed hopeless that I could ever reascend. Nor did I, by waking, feel that I had reascended.”

This isn't dreamlike in the contemporary sense, where "dreamlike" often functions as a vague stand-in for surreal. It's dreamlike in the literal sense, structured by association rather than argument, charged with emotional weight that exceeds explanation, and constantly slipping away the moment it feels graspable.

Addiction Without Resolution

There is no redemptive arc in Confessions. There’s no final insight, no dramatic fall and rise. In fact, De Quincey never truly frames his relationship with opium as a problem to be solved. He discusses the consequences: insomnia, melancholy, a withering of vitality. But he doesn’t pathologize the impulse. Nor does he deny the power of its pleasures. That complexity is rarely permitted in contemporary narratives of addiction, which tend to flatten the experience into a sequence of poor choices and heroic recoveries.

De Quincey does something more difficult. He shows how addiction reshapes the very field in which choices occur. He doesn’t excuse himself. But he doesn’t condemn himself either. And he certainly doesn’t apologize for his mind’s willingness to follow the trail of sensation wherever it leads.

No, its not a narrative failure but an ethical position. It asks us to stay with ambivalence. To consider what it means when pleasure and suffering become entangled. To read not just for outcomes, but for interior states. For moods, for patterns of attention, for the textures of consciousness as it fractures and reforms under pressure.

Language as Territory

What often gets missed in readings of De Quincey is how formally ambitious the writing is. The prose isn’t simply descriptive. It’s a space the reader has to inhabit. Sentences elongate until they feel oceanic. Subordinate clauses stack up like dream images. There’s a deliberate excess, a refusal to economize, that matches the psychological subject matter. Something rather structural and not ornamental.

And yet, within that density, there’s precision. De Quincey is acutely aware of rhythm, tone, cadence. The shifts in his diction mirror the shifts in his mental state. He modulates between Latinate formality and sudden, raw emotional outbursts. This tonal instability mirrors the way opium dislocates feeling from its usual coordinates. Emotions arise unbidden, disproportionate, untethered.

“The opium-eater loses none of his moral sensibilities or aspirations. He wishes and longs as earnestly as ever to realize what he believes possible, and feels to be exacted by duty; but his intellectual apprehension of what is possible infinitely outruns his power, not of execution only, but even of power to attempt.”

The mind, for De Quincey, is not a static organ. It’s a system of moving parts. And when the drug interrupts its ordinary functioning, the result isn’t just disorder - it’s a different kind of order altogether. One that can’t be represented by cause and effect, or by conventional narrative structures.

Memory Without Distance

One of the most affecting threads in Confessions is De Quincey’s relationship to memory. He doesn’t treat memory as a record, or even as a reconstruction. Instead, it behaves more like a haunting. Past scenes emerge uninvited, detailed yet decontextualized. The pain isn’t just that the past returns…it’s that it returns too vividly, crowding out the present.

There’s a particularly strange moment when he recalls early childhood experiences not as recollections but as full re-immersions. The scenes arrive complete, immersive, dislocated from chronology.

“The first notice I had of any important change going on in this part of my physical economy was from the reawakening of a state of eye generally incident to childhood, or exalted states of irritability.”

This separation is important because Opium seems to reorganize the memory and not just aid it. The boundaries between memory and dream dissolve. Emotional resonance takes precedence over factual sequence. What matters isn’t whether something happened, but how it continues to act on the psyche.

Where the Reader Stands

It’s not easy to locate yourself in this book. De Quincey doesn’t address the reader as a confessor, or as a friend. He isn’t trying to be understood in the therapeutic sense. But there is a strange intimacy in the writing. Yes, partly because he reveals private information, but also because he allows us into his perceptual field. He lets us drift alongside him, through the unstable territories of dream, delusion and intellectual wonder.

What he seems to ask is not for sympathy or judgment, but for participation. Not in his addiction, but in the act of seeing what the mind becomes when it’s no longer anchored by the assumptions of health, stability and realism. There is no firm interpretive ground here. Only motion. Ambiguity. And the occasional flare of insight that vanishes as quickly as it came.

And If We Don’t Look Away…

What Confessions ultimately offers isn’t a theory of addiction, or a moral account of suffering. It offers an extended meditation on the instability of inner life. On how easily the self disassembles under the pressure of sensation and time. On how language, when stretched and bent by altered perception, can begin to reveal its own limits.

De Quincey doesn’t deliver conclusions. He opens thresholds. And those thresholds are as unsettling as they are strangely familiar. Because if we’re honest, most of us know something about losing track of time. About memory arriving uninvited. About the strange interiors that open up when the ordinary world goes quiet.

He simply stayed there longer than most. And came back with pages.

Note: This essay is a literary meditation on Thomas De Quincey’s work, and should be read as such. Neither the writing nor its author intends to romanticize addiction or encourage drug use.

Have you ever experienced a moment where time, memory or identity felt unstable? What brought it on?

Until next time!❤️

This was a fascinating read, and so well written! Excellent work, thank you for sharing!